Every living language needs God’s Word. No people group is too small to matter.

excerpt from Until There Are None, Bible Translation, Life Transformation, and Seed Company’s First 25 Years, ©2018

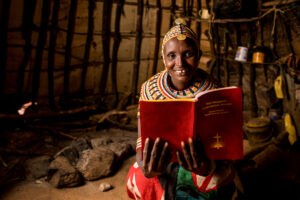

Makoma People Learn Jesus Speaks Their Language

The Makoma people had seen the “JESUS” film before, but not in their mother tongue. It hadn’t really made sense. But now a team of translators was drafting the film’s script into their language.

The recording of the script was complete, and the team scheduled a trial run to check its quality. Only translators and voice actors were expected to attend—about 20 to 25 people in total. They didn’t have a proper screen but planned to project the film onto a guesthouse wall.

But word got out about the viewing.

500 people showed up and crammed into tight quarters, eager to watch.

And this time, they understood. The message of Jesus was no longer foreign; he spoke their language. And when the film ended, half of the viewers responded with decisions to follow Christ.

That was 2016. A few years earlier, this small people group in western Zambia had no Scripture in their language, and they weren’t the only ones. Yet a national Bible organization stated, “Our country has no remaining languages that need a translation.”

When asked about this small language group, they said, “They’re too small to count.”

In 2008, Seed Company Field Coordinator Stuart Young was just a newbie when he crossed paths with South African missionary, James Lucas. They met at the Wycliffe office in Australia. James was taking a crash course in translation principles. He wanted to translate discipleship training materials into the languages of some pastors in western Zambia.

“You may find it’s a little more complicated than you think,” Stuart told him. “If you need help, here’s my card.”

Pleas for God’s Word

Six months later, Stuart got a call.

Soon, he was in Zambia talking with James and his wife about Bible translation needs. Zambia was already a well-developed country, but progress virtually halted at the edge of the Zambezi River.

During the wet season, the river stretches over 40 miles wide. Lying west of the river are thousands of villages with dozens of language groups. Churches existed, but not one had mother tongue Scripture.

Stuart and James met with several pastors from western Zambia. Each gave an impassioned plea, explaining why their language needed Bible translation.

“I’m trying to preach, but they don’t understand,” Stuart remembered one of them saying. “Let my language be the first choice.”

Four languages showed the most need. And churches in those areas already knew what they wanted—Luke’s Gospel, Acts, and the “JESUS” film.

Still, crucial pieces for starting the project remained missing. Stuart wondered how he could get such a complicated project off the ground.

Pieces of the Project Come Together

A couple of months later, he attended Seed Company meetings in Texas. During a coffee break, he struck up a conversation with an older man next to him he hadn’t met. His name was Wolf Seiler.

“So, what do you do?” Stuart asked.

“I’m a translation consultant,” Wolf replied. “I’ve been working with a translation team in Nigeria on the ‘JESUS’ film. But we’re nearly finished.”

Stuart was looking for this kind of person. He told Wolf about the project in Zambia. Surprised, Wolf said his daughter had just moved to Zambia. He’d been looking for a reason to go there, too.

Just like that, the project had a lead consultant.

But none of the languages had a writing system. Stuart also needed a linguist. Back in Australia, he received an unexpected visit from a former teacher who was working on a linguistics degree.

“I still need hands-on, practical experience,” she told him.

Stuart had just the spot for her.

Soon, she and a colleague were off to Zambia. The impossible project was starting to take shape.

At an initial workshop, another language community was added, but members of the group were hesitant. They weren’t sure their language was really a language. A majority tribe constantly belittled them with comments like, “That’s monkey talk. You’re human. Don’t talk like a monkey.”

The linguist analyzed their language. Soon they had a writing system and became part of the Mongu Cluster project. The workshop participants went back and told their people:

“We no longer need to feel ashamed. Now we know our language has status and dignity.”

Take a 360-degree tour of the Mongu Cluster project:

Working as One

Multiple translators from five language groups began attending regular workshops. Some traveled more than 15 hours to get there. They walked, came by bicycle, ox cart, canoe, and bus. Despite long distances and difficult terrain, they all kept returning.

“This showed their confidence in the project and belief in the importance of the work,” James said.

Before the project began, the translators said they saw much fighting among various denominations. They worried about working with people from different church backgrounds and language areas, but soon their fears dissipated.

“We realized there is one Bible, one faith, one everlasting life,” one participant told James. “So we also worked together as one.”

When the translators returned home, they carried this spirit of cooperation with them.

Early workshops involved telling and writing down stories from the translators’ cultures. These workshops helped them analyze the unique sounds of each language, to ensure each alphabet and writing system was accurate.

Soon, workshop participants were translating the first-ever Scripture portion into their languages. Excitement soared as Luke 10:25–37, the Parable of the Good Samaritan, emerged in written form in the Fwe, Kwangwa, Makoma, Mashi, and Shanjo languages.

They were no longer too small to count.