Through intense prayer and unconventional thinking, a bold idea with few initial takers became the future of Bible translation.

Bernie May believed God wanted to do something different within the Bible translation movement. But the man who would become the first president of Seed Company wasn’t convinced he should be part of it.

Nevertheless, he was determined to “find out which way God was going, and go with him.” Hear the challenge from Bernie himself:

The year was 1992, and Bernie had worked with Wycliffe Bible Translators (WBT) since 1954. His 12 years as Wycliffe USA’s leader had just ended. At 60, he needed a break. But change was coming in Bible translation, and the Wycliffe USA Board, led by Chairman Peter Ochs, asked Bernie to spearhead the transformation.

“I’ll pray about it,” Bernie told him.

Bernie knew that change was needed.

Back in 1975, with nationalism on the rise globally, Wycliffe had established national Bible translation organizations around the world with a “three-self” concept: self-determining, self-propagating, and self-funding.

“They were real good at self-determining—they liked being in charge,” Bernie recalled. “They were OK with self-propagating to get more people. But the self-funding part didn’t work very well, and they kept depending on outside sources for funding.”

With a support system dependent upon raising money for, essentially, outsiders working in a nationalist climate, funding remained an issue into the 1980s.

“By the end of the decade,” Bernie said, “it just wasn’t working.”

A Bold Idea

As the 1990s began, John Bendor-Samuel was nearing the conclusion of his term leading the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) and surveying Bible translation’s long-term needs. He saw that Africa was different from other locations, already strong in linguistics and with advanced capabilities for Bible translation.

Accelerating Bible translation in Africa and, subsequently, other regions would require a new strategy. In 1991, John pitched his final challenge to the joint board of directors for Wycliffe and SIL: find a way to fund the national organizations.

Those boards soon turned to Wycliffe USA to develop a program to provide that funding. The Wycliffe USA board knew that Bernie could find a way.

“A brilliant visionary.” That’s what Hyatt Moore, Bernie’s replacement as Wycliffe USA president, called him.

“Bernie May,” said David Bendor-Samuel, John’s brother and SIL vice president at the time, “was very open to opportunities which didn’t really look like opportunities.” Bernie took an eight-month sabbatical to pray and travel the United States with his wife, meeting with donors he had developed relationships with through WBT.

They were mature Christians, he said, who understood missions.

A New Strategy

He intentionally sought the input of what he called “outsiders”—successful business leaders working outside of Bible translation yet also involved in and knowledgeable of the movement. Bernie leaned heavily on Ochs and Roger Tompkins, who, like Ochs, was a businessman who had chaired the Wycliffe USA board. A strategy began to develop, and each person Bernie visited encouraged him to move forward with his vision.

I’ll do it, Bernie decided.

With Hyatt’s full support, a new organization spun out of Wycliffe USA for the purpose of accelerating Bible translation. On January 1, 1993, an experiment began that would become known as Seed Company. Bernie led the way from his desk inside a converted broom closet at Wycliffe USA headquarters in California. And it launched on a model drastically different for the Bible translation movement: funding projects, rather than missionaries, through individuals capable of investing, in some cases, 100 times the typical contributions that supported Wycliffe’s work.

Investing was a key word. During his sabbatical, Bernie had noticed Wycliffe’s donor base changing its collective mindset. Donating was giving way to investing, and Bernie’s strategy included an outcome-based framework with increased accountability. Project management became a priority.

“An investor expects to be part of the process and see results,” he said.

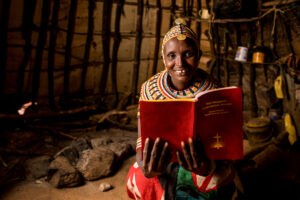

The new model centered on partnering with national Bible translation organizations. Locals would help lead—and would own—projects to translate Scripture into their heart languages.

“I had a sense that’s what God wanted us to try,” Bernie said. “I could sense God in it.”

Not everyone could.

“There were a lot of people who didn’t think Seed Company was even needed,” he explained.

Bernie met with SIL’s area directors for Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Only the director of Africa—the area that was a pioneer in the need for national-led translation—embraced his proposal.

The area director for Asia, who was a close friend, told Bernie he appreciated the approach but didn’t think it would be embraced there.

Bernie returned home asking himself, Why am I doing this?

After all, he had designed the model specifically to better assist field partners. He had anticipated broad support for this new type of partnership. Yet the Americas and now Asia—Bible translation’s largest field of the future—had turned him down.

Maybe I’m doing the wrong thing, he thought. Maybe it’s not going to work. But he set to work anyway.

Bernie targeted 10 projects where he believed the strategy would succeed. Then, he began approaching businessmen he hoped would invest $10,000 a year for up to 10 years. He only had to contact 10 potential investors, because all said yes.

Soon after that, Bernie shared his vision with Ken Taylor, founder of Tyndale House Publishers and creator of The Living Bible.

Prayer and Unconventional Thinking

“I want to encourage you,” Ken told Bernie. “I’m going to give you $100,000 each year for the next five years.”

“I’m encouraged already,” Bernie said.

The experiment worked, and in 1998, Seed Company incorporated. Ochs was the first chairman of the board.

“He was a very, very key player,” Bernie said. “He had a lot of good ideas. A lot of what Seed Company is doing now and the early policies that made us distinctive came from Peter. He made us function like a business, and none of us knew how to do that.”

And now, more than three decades after its start in a broom closet, Seed Company not only operates in the places that initially said “no, thanks” to Bernie, but also in locations once thought too risky, and even impossible, for Bible translators to work.

Furthermore, the Seed Company model, known as the Common Framework, is employed throughout the Bible translation movement. As a result, a movement once focused on the next group of languages needing Scripture is targeting the final languages.

Bernie reflected on Seed Company’s history by recalling his junior high days, when he ran track relays. The anticipation swelled with each baton handoff. The cheering increased as the finish line neared.

Spreading the gospel has been like a relay race. The Apostle Paul ran the first leg 2,000 years ago. Now, Bernie said, the race is in the final lap, and he relishes being part of the excitement.

“Here’s something that’s taken generations,” he said, “and we might be the generation that carries it over the line.”